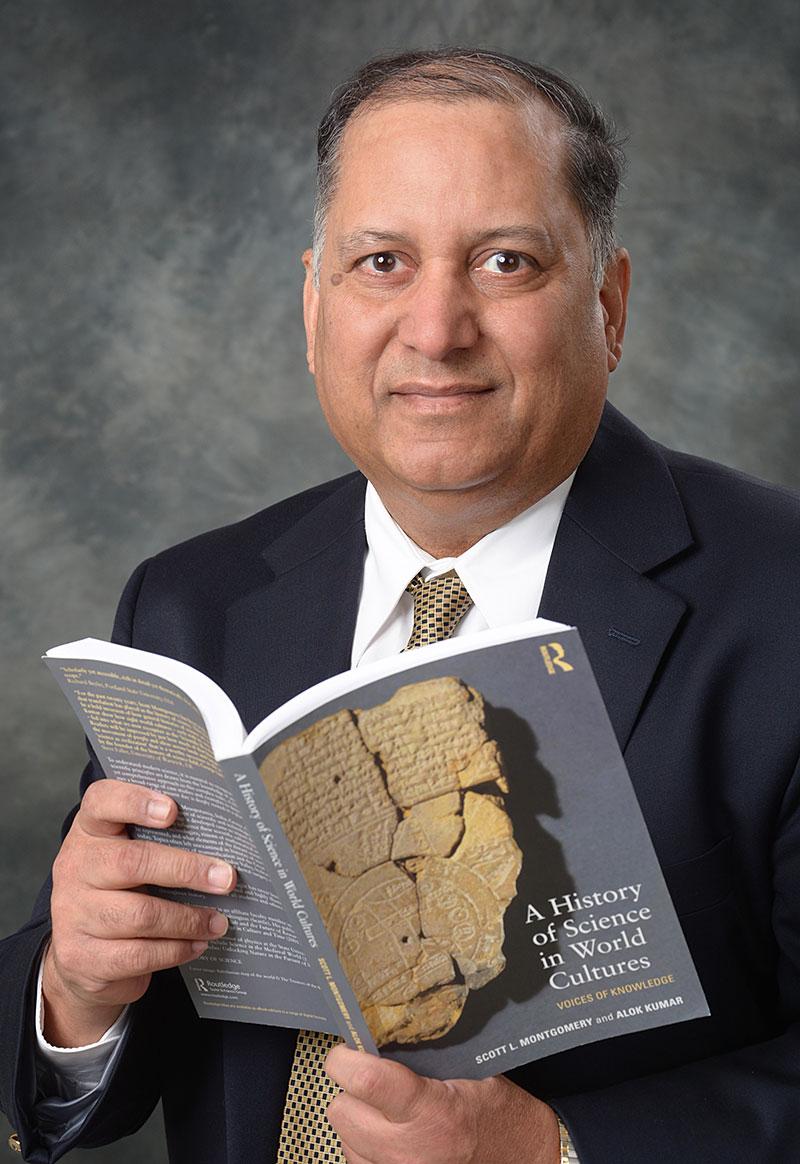

Science history re-examined—Dr. Alok Kumar of SUNY Oswego’s physics faculty long has maintained that the history of scientific discoveries has missed or dismissed the contributions of ancient civilizations. He and co-author Scott L. Montgomery seek to rectify such perceptions in a new book, “A History of Science in World Cultures: Voices of Knowledge.”

In a newly published book, SUNY Oswego physics professor Alok Kumar and co-author Scott L. Montgomery provide evidence that Europe’s scientific revolution depended profoundly on ideas and innovations passed down from ancient cultures.

“A History of Science in World Cultures: Voices of Knowledge,” published by Routledge, traces the origins of European scientific “discoveries,” demonstrating that many derived, at least in part, from much earlier work in China, India, Persia, Babylonia and other cultures. Reviewers have applauded the work of Kumar and Montgomery, a geoscientist and affiliate member of the University of Washington’s Jackson School of International Studies.

Eurocentrism in the teaching of science history “warps our understanding of the past and thus the present,” the authors write. “Scientific work and thought have never belonged to one race, one gender, one social class. Nor have they been confined to one time period or one culture or one part of the globe.”

Reviewer Steve Fuller of Warwick University in the United Kingdom wrote, “In a bold inversion of how general histories of science are normally written, Montgomery and Kumar show how eight world cultures—each with its own knowledge-producing traditions—fed into what we now recognize as the ‘Scientific Revolution’ of 17th-century Europe. Readers will be impressed by just how much of that history can be told simply by following the movement of people and ideas across lands and languages. The result is an account of ‘science as civilization’ that is a worthy successor to the project first laid down a century ago by the founder of the history of science field, George Sarton.”

Kumar, who follows up his 2014 book “Sciences of the Ancient Hindus: Unlocking Nature in the Pursuit of Salvation,” and Montgomery, a prolific author, consulted a vast number of primary documents to support their thesis.

“I realized as a young teacher that the history of science that we teach was incomplete and, if I use a stronger word, wrong,” Kumar said.

Ancient contributions

Students need to know, Kumar and Montgomery say, that Islamic cultures gave us such words as guitar, nadir, zenith, elixir and magazine; that the sine function and decimal-place notation came from ancient India; that the Sumerians observed a seven-day week; that Babylonians developed the 60-minute hour; that Mesoamericans predicted solar eclipses and used vulcanized rubber.

The new book cites hundreds more examples—from the chemistry of mummification in Egypt to hydraulic engineering in China, from urban planning in the Indus Valley to dental surgery among the Mayans—to show that “cutting away these pre-modern roots leaves a damaged view, one that risks the provincial satisfaction of a colonialist eye.”

The two authors’ collaboration began five years ago, but for Kumar, the project has been about 25 years in development. He said he’s been gratified by the reception among scholars for a book written to attract a general audience and serve as a textbook.

One important way Kumar thinks the book resonates with scholars and with average readers is the consistent notion that scientific thought and learning for thousands of years and in cultures the world over have sought to bring people closer to their religions’ supreme being.

“All of these cultures used science and technology as tools to enhance their knowledge of the creation and the Creator,” he said.